top of page

Bengisu Üstay

London / İstanbul

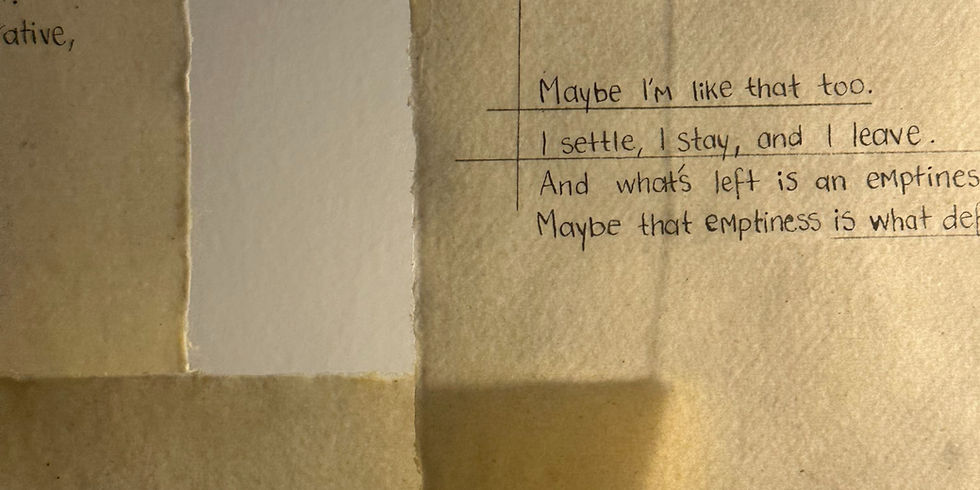

I Settle, I Stay, and I Leave / Yerleşiyorum, Kalıyorum, Sonra Çekip Gidiyorum.

his series of handwritten manuscript pieces explores themes of ecological memory, interspecies authorship, and the fragility of communication across both material and conceptual boundaries. Written in iron gall ink on paper and coated in beeswax, the pieces are intentionally momentary, caught between preservation and decay.

Through poetic reflection, the pieces question authorship, value, and the human position in language-making. Lines emerge from imagined entanglements with wasps, oaks, and gall formations that are minor ecological dramas that often go unseen.

The use of beeswax and iron gall ink makes the text both luminous and corrosive. Over time, the ink eats into the paper, yet it may be protected by the wax, creating a delicate negotiation of survival. The work refuses clarity, opting instead for quiet intensity and unresolved tension.

Through poetic reflection, the pieces question authorship, value, and the human position in language-making. Lines emerge from imagined entanglements with wasps, oaks, and gall formations that are minor ecological dramas that often go unseen.

The use of beeswax and iron gall ink makes the text both luminous and corrosive. Over time, the ink eats into the paper, yet it may be protected by the wax, creating a delicate negotiation of survival. The work refuses clarity, opting instead for quiet intensity and unresolved tension.

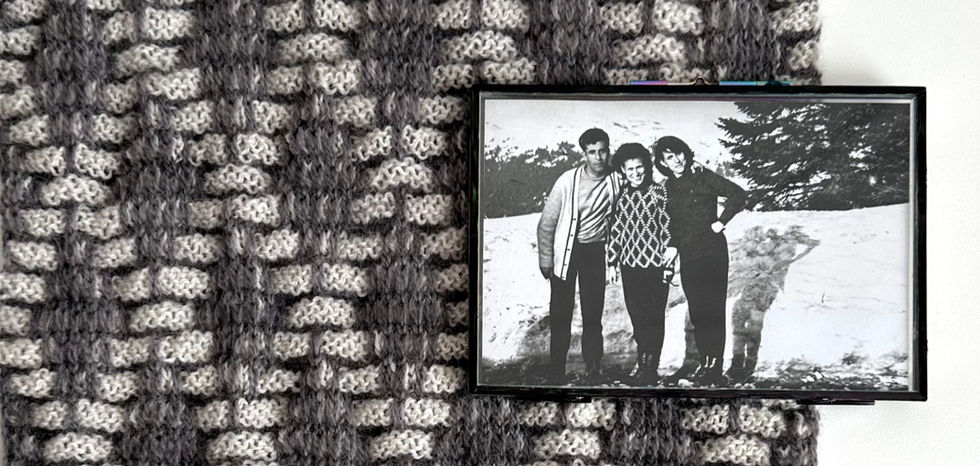

There was more to it but I can barely remember now. / Daha ne motifler vardı da unuttum şimdi ben.

“There was more to it, but I can barely remember now.” is a knitted reconstruction of a sweater pattern my grandmother created for herself in the early 1960s, just before she got married. She once told me that before domestic responsibilities took over, she had the time to knit for herself, choosing complex, carefully calculated patterns. After marriage and children, she never made anything so intricate again.

Sixty years later, I asked her to recall the pattern from memory. From her oral recollection, I reknitted a fragment using wool I dyed with iron gall ink. Historically used in archives and manuscripts, iron gall ink represents both preservation and slow erosion. In this work, it functions as both a dye and a metaphor. It reflects how memory and labour, especially within domestic spaces, are preserved imperfectly and often remembered with fragility.

Sixty years later, I asked her to recall the pattern from memory. From her oral recollection, I reknitted a fragment using wool I dyed with iron gall ink. Historically used in archives and manuscripts, iron gall ink represents both preservation and slow erosion. In this work, it functions as both a dye and a metaphor. It reflects how memory and labour, especially within domestic spaces, are preserved imperfectly and often remembered with fragility.

The Size of a Gap / Bir Boşluk Kadar

The Size of a Gap explores the relationships between humans and other species by questioning the ways in which these beings are defined, named, and categorised. The work centres on the interaction between the gall wasp and the oak tree, a relationship that is often overlooked or simplified through human frameworks of utility and harm. By focusing on the traces left inside a gall and the life that briefly occupies it, the installation reflects on the forms of living together, leaving a mark, and parting ways.

The piece invites viewers to reconsider dominant classifications such as ‘harmful’ or ‘useful’, which are frequently imposed on non-human life. These distinctions, though presented as objective, are shaped by anthropocentric perspectives that rarely allow room for ambiguity or mutual transformation. By bringing together a micro-scale life cycle with broader structures of meaning. The Size of a Gap suggests that even the smallest, quietest forms of existence can challenge the ways we perceive, categorise, and relate to other forms of life.

The piece invites viewers to reconsider dominant classifications such as ‘harmful’ or ‘useful’, which are frequently imposed on non-human life. These distinctions, though presented as objective, are shaped by anthropocentric perspectives that rarely allow room for ambiguity or mutual transformation. By bringing together a micro-scale life cycle with broader structures of meaning. The Size of a Gap suggests that even the smallest, quietest forms of existence can challenge the ways we perceive, categorise, and relate to other forms of life.

Inter-lineage / Nesiller Arası

Inter-lineage centers on the entangled relationships between humans and nature, the transmission and questioning of inherited knowledge, and the mutual dependencies between living beings. The work reconsiders the teachings and ecological curiosity passed down from the artist’s grandmother who was formerly a nature studies teacher through a critical lens, foregrounding the often-overlooked influence of nonhuman lifeforms and material agents on cultural memory and historiography.

At the heart of the piece lies the complex relationship between the oak tree and the gall wasp. The interdependence of these two species becomes apparent through the gall’s formation, a site where parasitism and symbiosis blur. Historically, ink made from oak galls has played a crucial role in the preservation and transmission of human knowledge. Yet, ironically, this same ink gradually corrodes the paper it inscribes, revealing the limits of human control over nature and the fragile temporality of our cultural legacy.

Through this intricate web of relationships, Inter-lineage invites reflection on alternative modes of coexistence with companion species. Rather than offering fixed narratives, the work encourages viewers to explore from a non-anthropocentric perspective, redefining connections and imagining new ways of being together across species and generations.

At the heart of the piece lies the complex relationship between the oak tree and the gall wasp. The interdependence of these two species becomes apparent through the gall’s formation, a site where parasitism and symbiosis blur. Historically, ink made from oak galls has played a crucial role in the preservation and transmission of human knowledge. Yet, ironically, this same ink gradually corrodes the paper it inscribes, revealing the limits of human control over nature and the fragile temporality of our cultural legacy.

Through this intricate web of relationships, Inter-lineage invites reflection on alternative modes of coexistence with companion species. Rather than offering fixed narratives, the work encourages viewers to explore from a non-anthropocentric perspective, redefining connections and imagining new ways of being together across species and generations.

Undoubtedly, I am a high-frequency energy / Hiçbir bedel, hiçbir koşul istemeden

Hiçbir bedel hiçbir koşul istemeden / Undoubtedly, I am a high-frequency energy was developed in collaboration with Sriwhana Spong, as part of her wider body of work examining the intersections of embodiment, energy, and ritual.

Drawing from the transcript of a guided meditation in which trees serve as symbolic figures, the performance centers around the activation of two sculptural instruments: Instrument I (Sevgi and Bengisu) and Instrument J (Georgie) both created by Sriwhana Spong.

The instruments house found objects collected from across the city of Istanbul, hidden within their forms. Through choreographed performance, the chemical energy of the human body is translated into kinetic energy, subtly animating these embedded items and evoking layers of urban memory and material resonance.

Drawing from the transcript of a guided meditation in which trees serve as symbolic figures, the performance centers around the activation of two sculptural instruments: Instrument I (Sevgi and Bengisu) and Instrument J (Georgie) both created by Sriwhana Spong.

The instruments house found objects collected from across the city of Istanbul, hidden within their forms. Through choreographed performance, the chemical energy of the human body is translated into kinetic energy, subtly animating these embedded items and evoking layers of urban memory and material resonance.

No Place to Visit / Gezilemeyecek Görülemeyecek Yerler

The project No Place to Visit centers on sites within the Kaleiçi district, where the artist spent her childhood. While seeking to bring visibility to these overlooked spaces in the historic Hisar area, the work draws upon a deeply personal and cultural tool: the traditional handcrafts once practiced by the women of the neighborhood. These crafts, once subtle acts of presence and expression, become the project’s primary medium.

By subverting the familiar phrase “a place to visit,” the project questions what constitutes visibility, value, and memory in urban space. Through a deliberate inversion of this tourism-driven language, it opens a new route, one that sheds light on hidden histories and overlooked narratives.

Bringing together two forms of invisibility, the project turns this convergence into a strategy for visibility. In doing so, it touches upon broader themes such as the preservation of monuments and the transmission of cultural heritage.

By subverting the familiar phrase “a place to visit,” the project questions what constitutes visibility, value, and memory in urban space. Through a deliberate inversion of this tourism-driven language, it opens a new route, one that sheds light on hidden histories and overlooked narratives.

Bringing together two forms of invisibility, the project turns this convergence into a strategy for visibility. In doing so, it touches upon broader themes such as the preservation of monuments and the transmission of cultural heritage.

Peace with Identification

“Oktṓ” means eight and “poús” means foot in Latin. Octopus was named after the count of its legs. So what if it loses one of its legs? Is it still counted as an octopus?

In many cases humans have the tendency to think about nature as something they can possess or rule. So in the course of history the names that were given to many objects, beings and entities were chosen by humankind. But this doesn't necessarily have a negative impact since humans have the ability to learn and create languages. However the problem started when a group of nations went out to various kinds of parts of the world and forced their language upon people. Donna Haraway links this act with a much greater one which is named Plantationocene. She and Anna Tsing define Plantationocene as a consequence of first radical simplification and the elimination of categories of players. It calls out to false universality and it reminds the involvement of race and religion as Anna Tsing explains. This links the definition with colonialism perhaps. The dominance of “elite white male” and the classification which was made by comparing only white male with other beings. Plantionocene also suggests that simplification and substitution requires a world making which might be also linked with this dominance act of these white males and the universality created by eliminating others in order to make one homogeneous world. After people understood the changes which resulted from the Plantationocene and humankind’s traces on the world, Anthropocene was argued as the case. Anthropocene was “a term referring to transformative effects of human activities on Earth” as Haraway explains. Anthropocene also suggests that the change which has been done to Earth by humans started in the mid-eighteenth-century with the use of fossil fuels and steam engines. But like many people did in the past it draws a distinct line between polluted and polluter. It builds two sides one being humans and other being the whole different beings. This discrimination between nature which excludes humans and humankind which excludes the habitat they live in. This separation makes people look to nature in a different angle that somehow alienates all other entities.

In Codex Seraphinianus, Luigi Serafini depicted entities in a unique manner. He created an illustrated encyclopedia of an imagined universe. He illustrated in a manner similar to Medieval bestiaries and used a non-semantic language in the text. It is inspired by the superstition and myths of humankind. The Codex offers a different point of view than a common encyclopedia and exhibits a whole new way of describing the surroundings.

Peace with Identification takes the same method as Luigi Serafini did in Codex Seraphinianus and tries to illustrate surroundings with an alternative way. As the word “identification” advocates the act of naming someone or something, “Peace with Identification” encourages a way to make peace with identifying entities. With the knowledge of Anthropocene and Plantationocene the objects were named as different than they are called today. As Haraway says indigenous people are forced to learn southern idioms. White population insists on the unity of language but that could give birth to a monopoly and a homogeneous culture which lacks color and difference. She suggests that nurturing people contact may help players learn each other's idioms. This would bring diversity into the open and create a colorful language. Indigenous people have a lot to teach about nature and entities other than humans. Peace with Identification suggests that we have an option other than selecting a universal language to name or define entities. Shaping the words in a way that includes kinship and in a more Ecocentric rather than Humancentric approach may lead into thinking about nature since the power of language in meaning making and understanding surroundings can not be underestimated. By naming these objects in the work as peacemakers rather than protection from the environment, Peace with Identification links “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” Ursula Le Guin defines in her book. She argues that “We will not ‘beat’ climate change, nor is ‘nature’ our adversary”. This perspective of seeing oven gloves and winter gloves as objects with peacemaking purposes via touching rather than looking at heat and cold as enemies. Such mindset also emphasizes the importance of kinship as it suggests positive relationships between beings. A possible consequence of this kinship might bring a better awareness of surroundings and may lead to a more Ecocentric standpoint. The last image however concentrates on a more recent issue the world is currently facing. By taking one of the “protectors” from the recent COVID-19 virus and naming it as a peacemaker between humans and viruses, the name Peace with Virus makes the realization of the virus a part of people’s lives and possibly leads to an easier acceptance.

In many cases humans have the tendency to think about nature as something they can possess or rule. So in the course of history the names that were given to many objects, beings and entities were chosen by humankind. But this doesn't necessarily have a negative impact since humans have the ability to learn and create languages. However the problem started when a group of nations went out to various kinds of parts of the world and forced their language upon people. Donna Haraway links this act with a much greater one which is named Plantationocene. She and Anna Tsing define Plantationocene as a consequence of first radical simplification and the elimination of categories of players. It calls out to false universality and it reminds the involvement of race and religion as Anna Tsing explains. This links the definition with colonialism perhaps. The dominance of “elite white male” and the classification which was made by comparing only white male with other beings. Plantionocene also suggests that simplification and substitution requires a world making which might be also linked with this dominance act of these white males and the universality created by eliminating others in order to make one homogeneous world. After people understood the changes which resulted from the Plantationocene and humankind’s traces on the world, Anthropocene was argued as the case. Anthropocene was “a term referring to transformative effects of human activities on Earth” as Haraway explains. Anthropocene also suggests that the change which has been done to Earth by humans started in the mid-eighteenth-century with the use of fossil fuels and steam engines. But like many people did in the past it draws a distinct line between polluted and polluter. It builds two sides one being humans and other being the whole different beings. This discrimination between nature which excludes humans and humankind which excludes the habitat they live in. This separation makes people look to nature in a different angle that somehow alienates all other entities.

In Codex Seraphinianus, Luigi Serafini depicted entities in a unique manner. He created an illustrated encyclopedia of an imagined universe. He illustrated in a manner similar to Medieval bestiaries and used a non-semantic language in the text. It is inspired by the superstition and myths of humankind. The Codex offers a different point of view than a common encyclopedia and exhibits a whole new way of describing the surroundings.

Peace with Identification takes the same method as Luigi Serafini did in Codex Seraphinianus and tries to illustrate surroundings with an alternative way. As the word “identification” advocates the act of naming someone or something, “Peace with Identification” encourages a way to make peace with identifying entities. With the knowledge of Anthropocene and Plantationocene the objects were named as different than they are called today. As Haraway says indigenous people are forced to learn southern idioms. White population insists on the unity of language but that could give birth to a monopoly and a homogeneous culture which lacks color and difference. She suggests that nurturing people contact may help players learn each other's idioms. This would bring diversity into the open and create a colorful language. Indigenous people have a lot to teach about nature and entities other than humans. Peace with Identification suggests that we have an option other than selecting a universal language to name or define entities. Shaping the words in a way that includes kinship and in a more Ecocentric rather than Humancentric approach may lead into thinking about nature since the power of language in meaning making and understanding surroundings can not be underestimated. By naming these objects in the work as peacemakers rather than protection from the environment, Peace with Identification links “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” Ursula Le Guin defines in her book. She argues that “We will not ‘beat’ climate change, nor is ‘nature’ our adversary”. This perspective of seeing oven gloves and winter gloves as objects with peacemaking purposes via touching rather than looking at heat and cold as enemies. Such mindset also emphasizes the importance of kinship as it suggests positive relationships between beings. A possible consequence of this kinship might bring a better awareness of surroundings and may lead to a more Ecocentric standpoint. The last image however concentrates on a more recent issue the world is currently facing. By taking one of the “protectors” from the recent COVID-19 virus and naming it as a peacemaker between humans and viruses, the name Peace with Virus makes the realization of the virus a part of people’s lives and possibly leads to an easier acceptance.

Shared Rituals: Reimagining the Depas Vessel

This design piece draws inspiration from the depas amphikypellon, a distinctive two-handled drinking vessel prevalent in Early Bronze Age Troy (circa 2500–2000 BCE). These vessels, often associated with communal rituals and feasting, are characterized by their tall, slender form, dual handles, and absence of a flat base, rendering them unsuitable for resting on surfaces. Recent archaeological studies have confirmed their use in wine consumption, with chemical residues indicating the presence of succinic and pyruvic acids, byproducts of grape fermentation .

In reimagining the depas, this piece emphasizes its ritualistic and communal aspects. The design features two handles, facilitating shared use in a circle, symbolizing unity and collective experience. The absence of a flat base challenges conventional functionality, highlighting the vessel's ceremonial purpose over practical use.

This reinterpretation invites reflection on the role of shared rituals in fostering community bonds, drawing parallels between ancient practices and contemporary social gatherings.

In reimagining the depas, this piece emphasizes its ritualistic and communal aspects. The design features two handles, facilitating shared use in a circle, symbolizing unity and collective experience. The absence of a flat base challenges conventional functionality, highlighting the vessel's ceremonial purpose over practical use.

This reinterpretation invites reflection on the role of shared rituals in fostering community bonds, drawing parallels between ancient practices and contemporary social gatherings.

bottom of page